Many manufacturing business owners are of an age where they realize they need to sell their manufacturing business while they’re young enough to transition it to ensure its continuity. But sometimes, they’re not quite ready. These owners often face two hurdles:

- They need to grow their business a bit more to support their retirement. But, they might not want to re-invest for the growth they need so close to retirement.

- They’re not exactly ready to retire yet. They want to keep working, but maybe not at the same level or maintaining the same schedule.

There’s an option available in selling a manufacturing business that could double your net retirement dollars, and it’s likely an option you didn’t know you had.

Many manufacturing business owners assume that they must completely exit or sell the entire company. Not true.

There are companies that will buy either a controlling or noncontrolling interest in manufacturing companies rather than the entire company. Why would they do that?

There are many reasons manufacturing companies would agree to complete a partial acquisition. Here’s what’s in it for them:

- Get machining capabilities that they don’t have.

- Be able to offer their customers more services.

- Gain skilled workers.

- Easing into a complete acquisition may be better for the employees.

- If the current owner maintains equity, it ensures the proper transition of the company.

So how does this work, and what are the steps?

Step #1 Valuation

The first step in selling a manufacturing company, whether in whole or in part, is to determine its value. The valuation should be completed by someone who understands manufacturing and is considering more than just the tax returns. Here’s a good resource on 15 things that affect value.

Step #2 – Determine How Much of the Company You Want To Sell

Once a go-to-market price is established for the business, the seller must determine the amount of equity he is willing to part with. This is always connected to the amount the owner wishes to step back from the business. It’s different for everyone.

Step #3 – Go To Market

The company is then marketed in the same way it would be if the entire business was on the market, except the aim is to obtain a partial sale. The value is based on a percentage of the entire company valuation.

CONFIDENTIALITY WHEN SELLING A MANUFACTURING COMPANY

When we talk about marketing a manufacturing company, it’s important to note that confidentiality needs to be maintained. Here’s a resource on how confidentiality should be maintained during the process.

Step #4 – Finding The Right Partner

This step requires that potential candidates be vigorously vetted, both professionally and financially. However, in a partial sale, the vetting can’t end there. You also need to consider whether the acquiring company has similar values and culture. If you’re giving up equity, you always need to aim for getting more than money. If your company lacks a sales and marketing function, the acquirer should have that. If you’re aiming to increase sales and EBITDA before making a complete exit, the acquirer should have a history of growing companies. Never trade equity for ONLY money.

Step #5 – Negotiating The Deal & Ensuring Your Future Exit

If you’re accepting a partial sale, you need to be legally protected so you have a say in how the company is run. You also need to have a pre-determined exit path for the remaining shares when you’re finally ready for that fishing boat or spending more time on the golf course. These items are easily accomplished with shareholder and buy-sell agreements.

SO HOW CAN THIS DOUBLE MY RETIREMENT DOLLARS?

This is all about who you partner with and what they can add to the company. Perhaps you’ve grown your company to the best of your ability, but you hit a plateau that you can’t climb beyond. Or perhaps you need or want a larger liquidity event, but you’ve been in business so long that you just don’t have the energy to navigate the desired growth.

We’ve seen acquirers take a business from $10 Million to $100 Million in about five years. But for the sake of argument, let us look at what would happen with less robust growth.

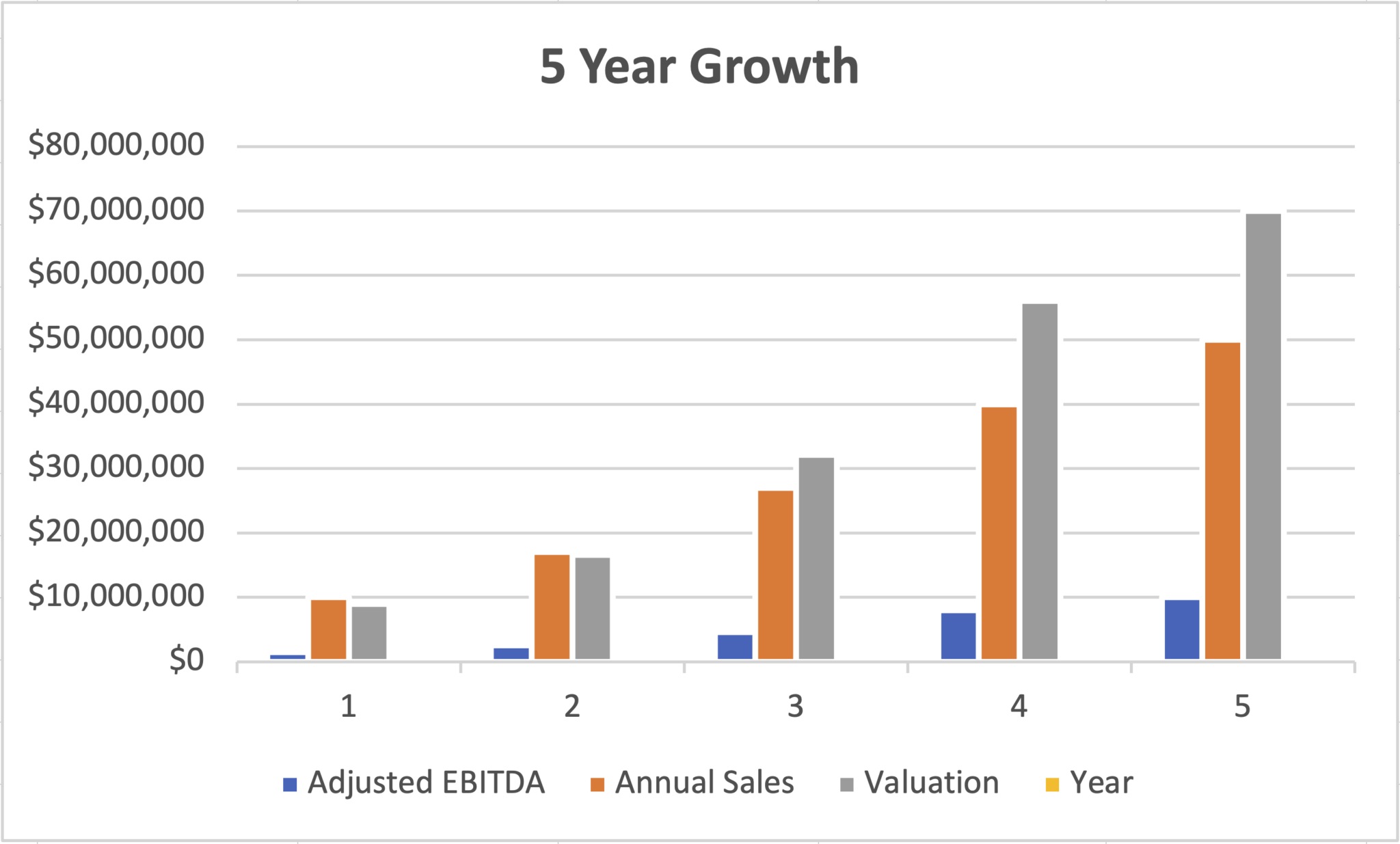

The chart below shows sales at $10MM and growing to $50MM in five years.

During that same period, the value of the company has grown from just under $10MM to $70MM.

A manufacturing business owner selling 50% of the company in year one would get just under $5MM, but five years later, the second liquidity event would be $35MM.

WHAT ARE THE DANGERS?

The scenario outlined above only works if the acquiring entity is really adding value from a sales and business development perspective. Growth, as depicted above, costs money. If the retiring seller is not participating in the cost, they will likely not reap the full benefit of the entire reward. The seller’s risk tolerance must be negotiated into the contracts. There’s not one right or wrong way of doing this. A seller can obtain whatever works for their family and their comfort level.

The point of this writing is to highlight that it’s possible to sell a manufacturing company in stages, thus dramatically increasing the funds available for the seller’s retirement.